Welcome to Ceramic Review

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

Ceramic Review Issue 326

March/April 2024

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

March/April 2024

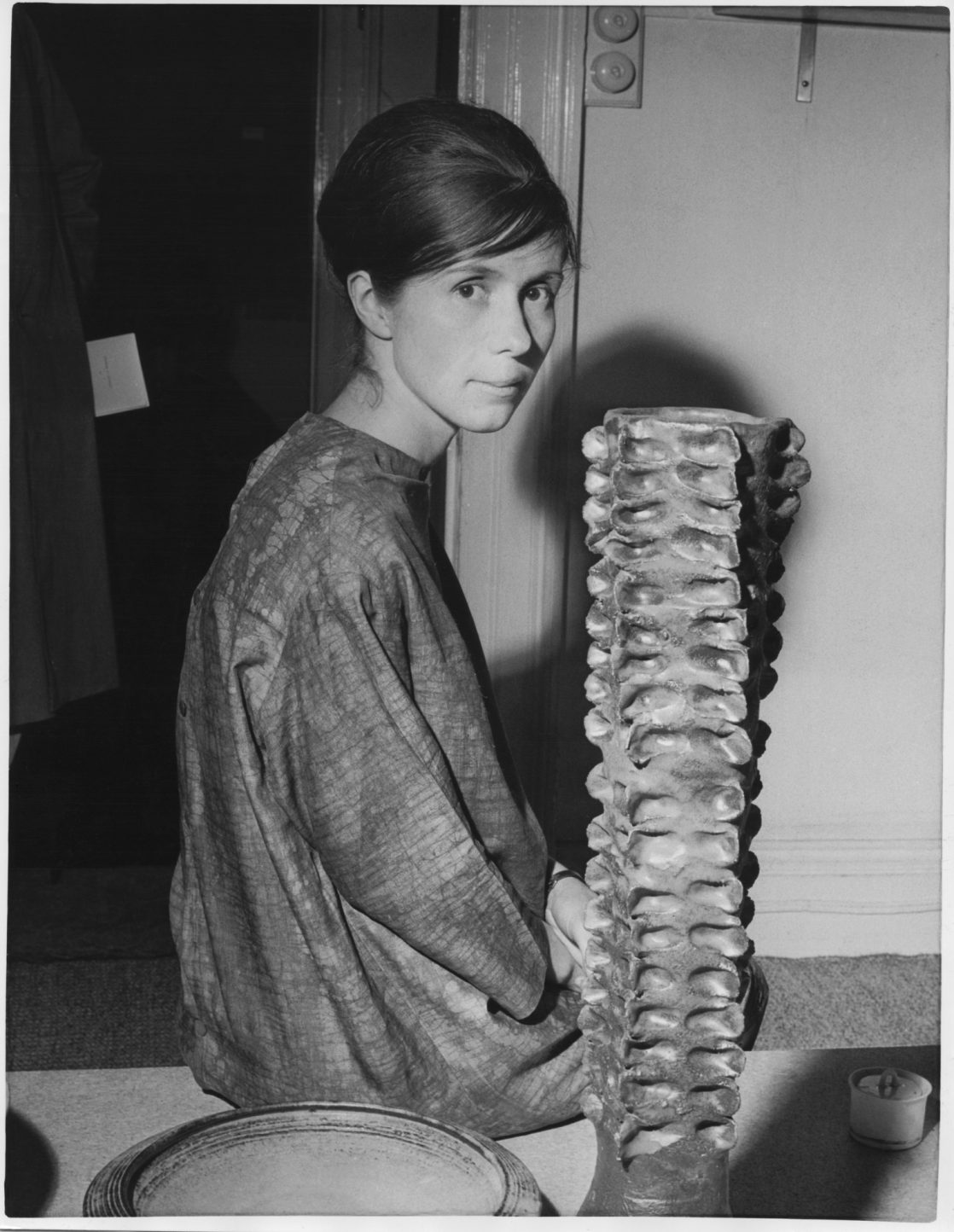

As a new exhibition of Gillian Lowndes work opens at the Holburne Museum, Beth Williamson examines her practice and place in the history of British ceramics

Gillian Lowndes (1936-2010) was one of the most adventurous and singular artists of the post-war period. Eschewing traditional studio ceramics, she created objects that haunt and disturb, still. The critic Peter Fuller once referred to her work as ‘trendy trash’, a dismissive alliterative label that adds nothing to an understanding of Lowndes’ place in the history of British ceramics. More helpful by far is the thinking of the writer and curator Amanda Fielding who understood it as ‘gutsy urban bricolage’, gesturing, perhaps, to the twisted destruction in the bombsites of post-war London.

Lowndes described herself as ‘a gatherer of impedimenta’, a materials-driven artists who repeatedly tested the limits of materials and processes to create fragile fragmented objects that are nonetheless imbued with emotive resonance beyond any clear visual or aesthetic associations. These are, as the critic William Varley recognised in Crafts in 1978, ‘objects of meaning and not merely of sensual or retinal charm’.

PROGRESSIVE POTTERY

Lowndes’s initial art school training at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London (1955–58) took place under Dora Billington at a time of huge shifts in art education and ideas about what art could be. Throwing and the dominance of the wheel yielded to hand building when Gilbert Harding Green took over as head of pottery in 1956, encouraging and supporting creative students. Along with Billington, Harding Green developed a progressive and open atmosphere for pottery at the Central appointing young artists to teaching and technical positions in what became a crucible for ceramic experimentation.

It was Gordon Baldwin’s talk of breaking the rules that excited Lowndes, she said later. A period of radical departures in ceramic practice, led by visionary artists and guided by the openness of the Central School’s then Principal William Johnstone and burgeoning ‘Basic Design’ training in the school, this laid the foundations for Lowndes’s thrilling developments in ceramics.

Her teaching, learning and making continued to develop in a number ofseveral places – the Central, Brighton College of Art, and West of England College of Art, for instance. In 1966 she set up home with Ian Auld where they built a shared a studio. At this time, she was making hand shaped pinch pots, multi-necked vases and sculptural wall panels that looked more to developments in modern art than the history of ceramics.

It would be the late 1960s before Lowndes’s work began to be recognised alongside her peers in exhibitions and publications including Tony Birks’s important survey The Art of the Modern Potter and Michael Casson’s Pottery in Britain Today, both published in 1967, as well as her inclusion in the V&A’s exhibition Five Studio Potters, which toured from 1969.

NEW OUTLOOK

Lowndes was looking at non-Western art at the British Museum even before she and Auld moved to Nigeria with their young son in 1970. Guided by Ladi Kwali, the family visited the Pottery Training Centre at Abuja (established by Michael Cardew in 1951). However, Lowndes looked less to ceramics and more to other objects such as wooden sculptures, head dresses, textiles and masks, something that fundamentally shifted her outlook and approach.

Upon her return to England in 1972, and over the following years, Lowndes’s focus moved away from the vessel and sculptural forms in clay. Instead, she developed a mode of making that did not discriminate materially, forming three-dimensional collage-type objects that included found objects and non-ceramic materials. Slip-dipped fibreglass and wire was subject to the vagaries of the kiln and mounted on melted brick platforms.

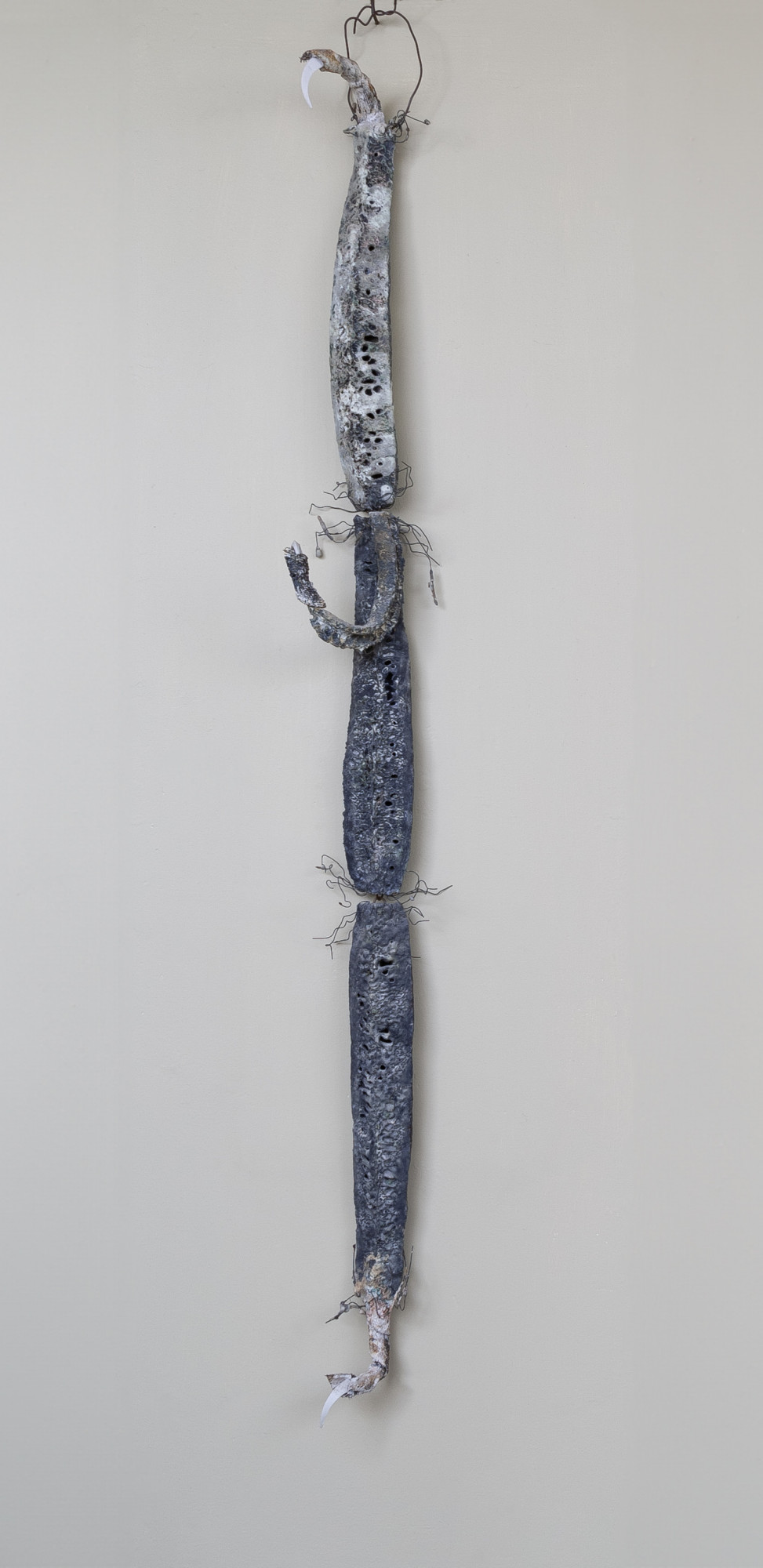

In the 1980s her Brick Bag series saw bricks transformed by process again, this time combined with pot shards and sometimes wall mounted. These works were followed by the Tail of the Dog series, a menacing string of works that gnaw at the subconscious. Avant-garde ceramics were on the rise and in 1986 Lowndes’s Collage with Cup and The Puff Adder cannot fly series both seriously complicated the categories of art and craft, ceramics and sculpture. Collage with Tomato Roots from the 1990s and the phenomenally powerful Hook Figure series of works, as well as Cage works, the Scroll series and Scrollscapes, became stranger still to behold. With Lowndes’s Tongue series in particular, the abject took material form in objects that ooze with Egyptian paste, slathered in Copydex and PVA, appended with rusty bulldog clips and twisted wire, pierced with metal tacks and sprouting thick dark hairs.

Undoubtedly, Lowndes emerged from an art training that opened up the possibilities of ceramics, enabled her to question the established rules and query the obvious. Yet, it was her fearless explorations in firing clay with other materials that allowed her to develop uniquely innovative sculptural forms.

This exhibition focuses on her work from the 1980s to the 2000s showing key examples such as Hanging Scroll and others from the Hook Figure series. These, along with a range of pieces including a small number of table-top and wall pieces reflect the breadth of her practice. These corporeal and vulnerable forms must be experienced at close quarters if their full poetic and evocative potential are to be met head on.

Images: courtesy of the Holburne Museum; Gillian Lowndes Archive; Dewi Tannatt Lloyd